Tomorrow Land

On July 17th, 1955 Disneyland USA opened its Tomorrowland exhibition, a place where technology and science pointed the way to a shiny, happy future of glorious inventions, space travel and nuclear-powered everything.

One of the key attractions was a collaborative project between Disney Imagineering and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the Monsanto ‘House of the Future.’ The almost five meter wide building, with its four square rooms cantilevering outwards from a central core, was made entirely from glass fiber reinforced plastic shells and showcased a vision of the year 1986. The center of the structure housed the kitchen and two bathrooms, while the living room, family room, master bedroom, and two small bedrooms occupied the wings. The ‘House of the Future’ and likewise Tomorrowland stood for a time and generation that was enthused by technological progress and fueled by an unprecedented economical wealth. The future appeared bright and full of excitement.

|

|

Obviously Tomorrowland was always meant to be a dream, set within an artificial environment, materializing the utopian concept of a better future based on expectations and hope. Nevertheless the idea it originated from and the vision it transmitted had tremendous value not only on a technological level but especially in what it meant for culture and society, a common, unifying belief in progress and prosperity.

Today we are once again witnessing technological change at a rapidly increasing pace, we have acquired economical wealth that would have been difficult a few decades ago, we’re healthier, we live longer and we can travel wherever our heart desires. Yet, when we think about the future it seems hard to imagine it as the bright and happy place showcased in the 1950s. Global warming, urbanization, dwindling energy resources, growing food demands, population growth, trash, migration, extinction of species, rising sea-levels, just to name a few, are challenges we are exposed to on a daily basis. Everything we do has an impact on a larger level, not because of our individual acts but because of their accumulation as a species. Obviously these issues aren’t new, they have been known since at least fifty years, yet back then we didn’t have the self-reflecting capacity to understand their truth.

But how can one now approach such challenges when the image we have of the future is unsettling and disturbing? How can one worry about putting the trash into the correct trash can while in the third world, there is so much trash that it has even created an artificial island? How can one speak about ecology if the trust in political leaders is overshadowed by their denial of scientific facts? Shouldn’t we instead be proud of what we have achieved and believe in a common, healthy future? Shouldn’t we create concepts and ideas that are pleasant and encouraging, and that carry seeds of hope and joy? Shouldn’t we reconsider our understanding of ecology as an ideology of constraint towards a quest for alternative (sustainable) solutions while increasing the quality and comfort of our environment? And shouldn’t especially we as architects, planners and designers provoke an optimistic look at the future, based on trust in our human capabilities and the willingness for collaboration and change?

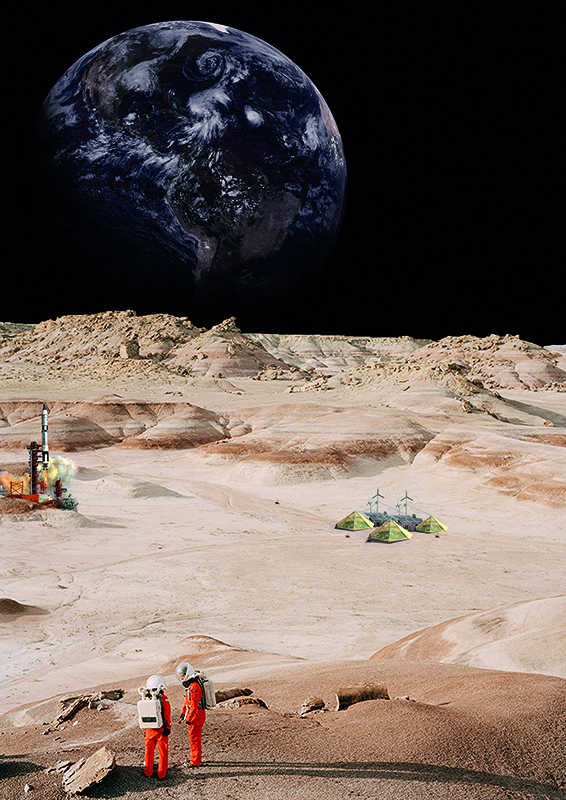

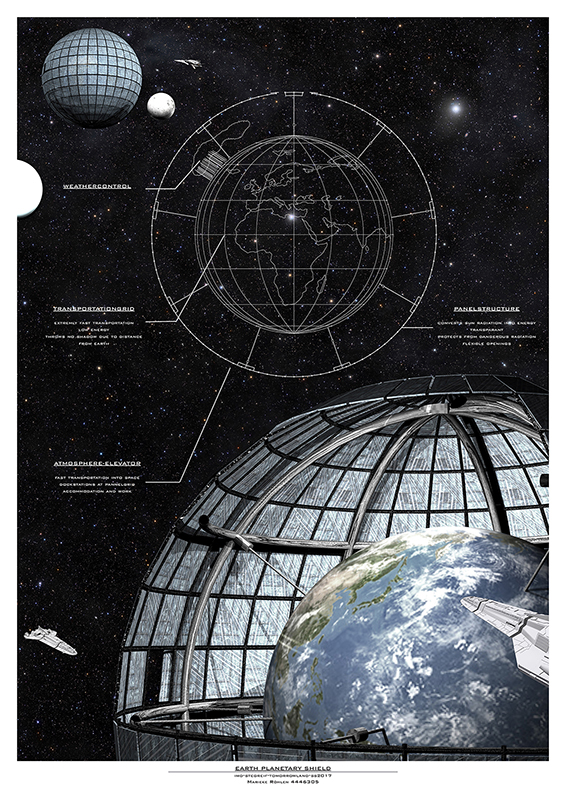

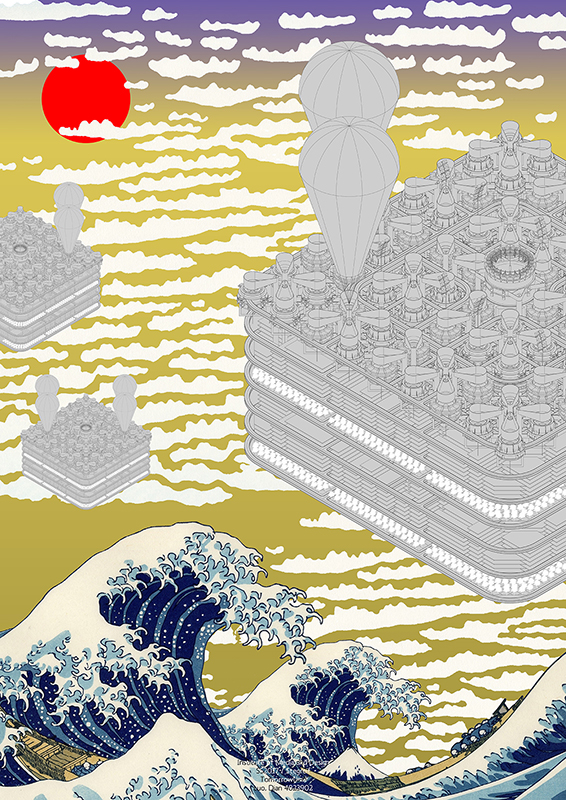

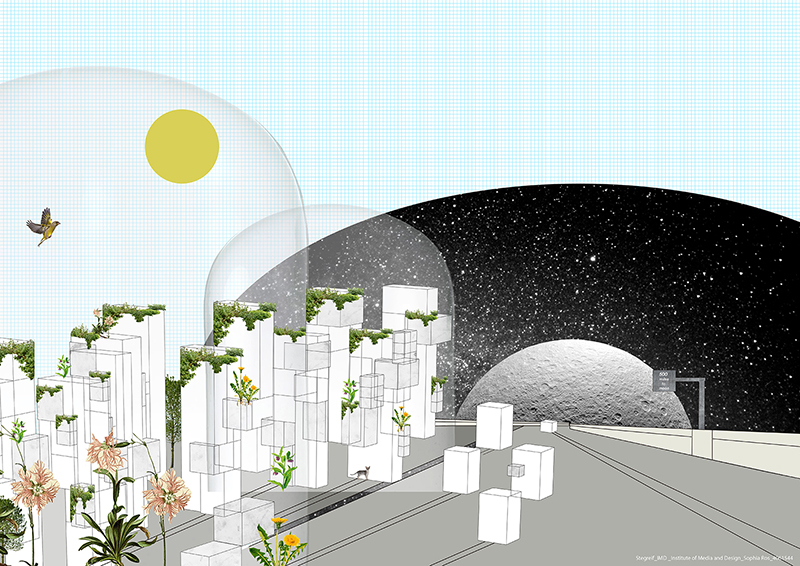

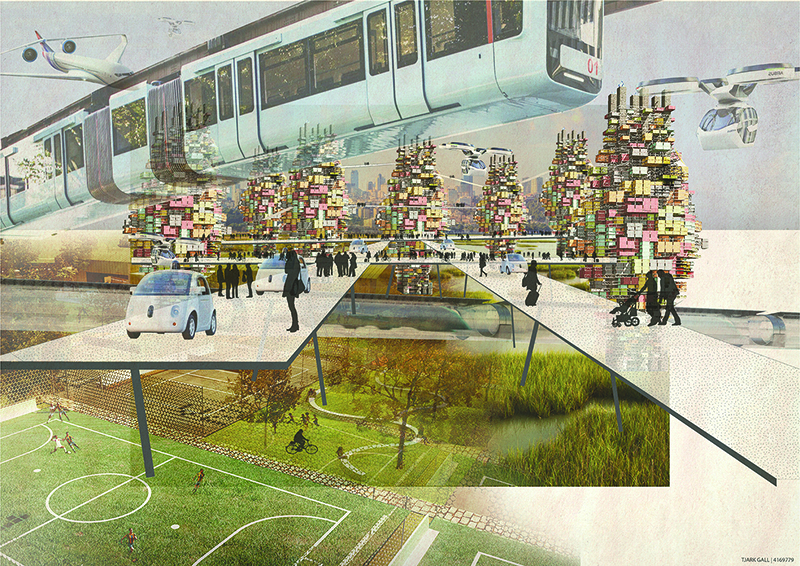

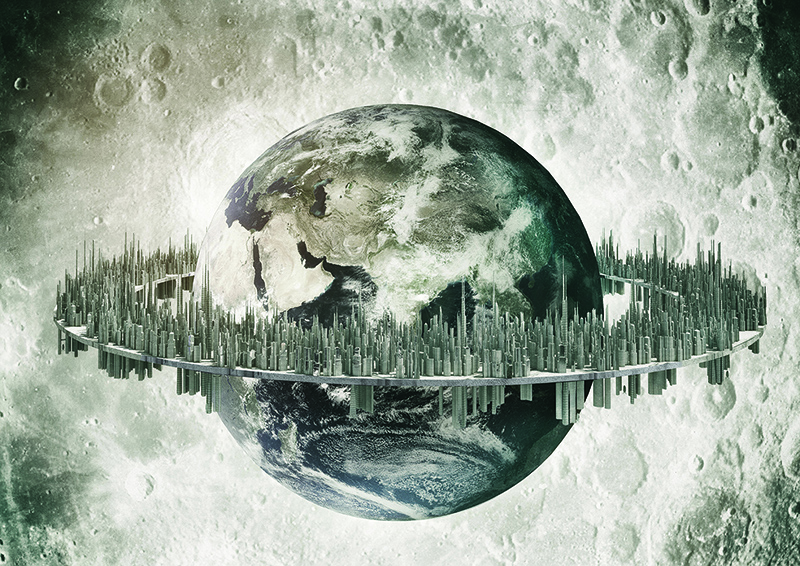

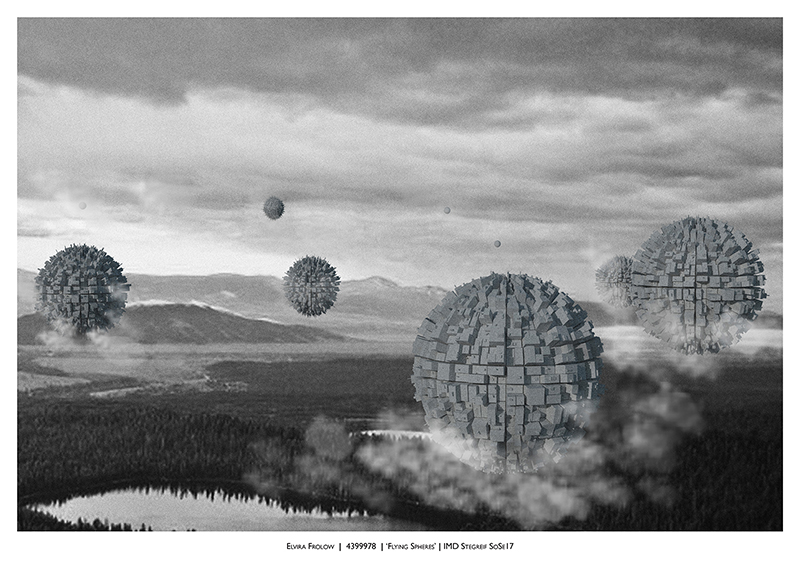

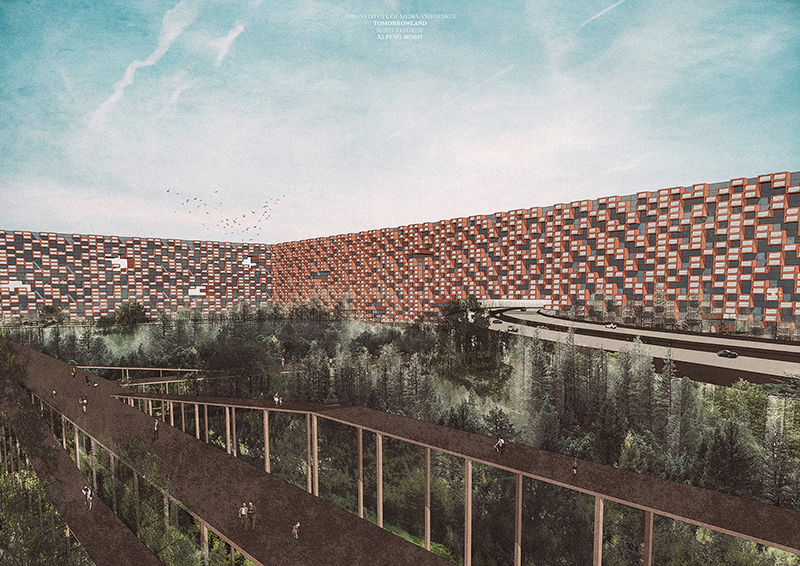

The task of this ’24h Stegreif’, held at the Institute of Media and Design, TU Braunschweig, was to create a high-resolution image, printed on A2, of a (architectural, urban, spatial) vision of the year 2050. A prototypical utopia, an optimistic ideal, a glimpse into one’s personal dream of tomorrow. The following is a selection of submitted proposals:

Mats Karl Koppe |

Britta Biehn |

Sofia Ramos |

Marieke Röhlen |

Stella Betz |

Dian Luo |

Sophia Ros |

Tjark Gall |

Christian Nicefor |

Sven Jonischkies |

Elvira Frolow |

Patrick Helmut Alois Schippan |

Fabian Schmoll-Klute |

Tilman Rickmers |

Jule Dersch |

Xi Peng |

Fabrizio Silvano